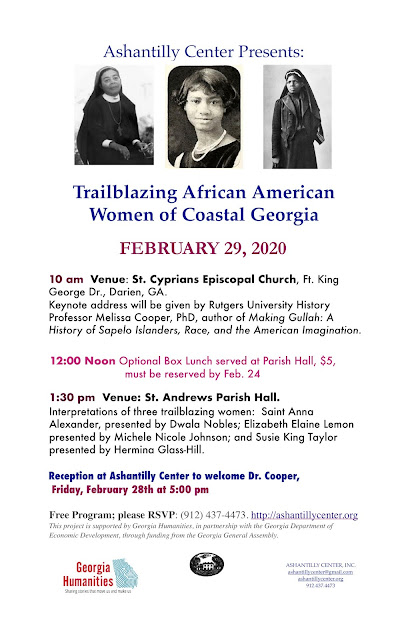

Note: This was a speech I delivered on Feb. 29, 2020, as part of Trailblazing African American Women of Coastal Georgia, a program presented by The Ashantilly Center at St. Cyprian's Episcopal Church and Parish Hall. -- MNJ

In my former life, as a newspaper journalist, I wrote a Family

column that was published weekly with my picture. So, when Black History Month

rolled around, I was bombarded with calls to speak at churches, civic groups, and schools.

The schools were my favorite because I actually loved the challenge of trying to hold the attention of squirming elementary

schoolchildren or engaging with middle or high school students who probably

would rather be somewhere else.

|

Elizabeth Elaine Lemon

|

I would often talk about family history, genealogy, one of

my passions. And I would explain to them that we all have heroes within the

branches of our family trees.During Black History Month we often celebrate people who

are larger than life household names – Martin Luther King Jr. and Harriet

Tubman … Malcolm X and George Washington Carver … and Frederick Douglass.

But many of the heroes in our families and in our

communities are of the unsung variety, the ones who worked behind the scenes,

and laid the foundation for others to build upon.

Elizabeth Elaine Lemon is one of those heroes.

She was born August 4, 1904, on Sapelo Island, Georgia, the

daughter of Thomas Lemon and Lula Walker Lemon.

Her family – her parents and brothers and sisters -- called

her “Bell.”

Bell’s early childhood, the early 1900s, was a time of

changes on Sapelo Island. The land that was once dominated by the Spalding

family, the island’s last major plantation owners, was purchased by Howard

Coffin, a Detroit auto man. Coffin moved to the island and rebuilt the former

Spalding “Big House,” transforming its tabby skeleton into a beautiful

Mediterranean-style estate.

The black people on Sapelo included the formerly enslaved

and their children and grandchildren. Many people on Sapelo worked for Howard

Coffin performing the same tasks they or their ancestors had performed during

slavery – cooking, cleaning, tending to the cows in the dairy or the flowers in

the greenhouse.

Bell would have undoubtedly heard stories about her grandfather,

James Lemon, who was born in 1828. He was one of several enslaved men on Sapelo

who ran away and joined the Union Army during the Civil War. He served in

Company A of the 33rd Regiment of the U.S. Colored Infantry.

His wife, Jane Cummings Lemon, ran away, too, along with other enslaved people, when the Spalding family evacuated Sapelo Island ahead of Union troops. According to James Lemon’s

pension records, he was granted special permission to leave the war to return

to Sapelo Island to check on his wife.

Young Bell would have no doubt heard these stories and many more, and probably

would have been aware of and experienced the injustice of Jim Crow and the racism always

present in black people’s lives long after slavery ended.

But she also would have witnessed what many little black

girls and boys saw in the early 1900s all across America … black people making

a way out of no way, creating opportunities for themselves, building communities,

working together in churches, civic organizations, fraternal organizations, working

as entrepreneurs and skilled craftsmen.

Bell would have known the value of education with the

island school playing a vital role in developing strong minds and character in

children who would grow up in a segregated world that did not value their worth.

Bell described her early education in an interview with

genealogist Mae Ruth Green in the early 1980s.

“The children learned phonics and had to memorize poetry.

In fact,” she said, “most of the poetry I know now, I learned on Sapelo

Island.”

Bell attended grades one through five on Sapelo Island, and

then continued her education at St. Athanasius Episcopal School in Brunswick. In

the summers, she said she would scrape up bus fare to go to Savannah in search

of work cleaning homes and doing other tasks for families.

“I would not spend more than a dime of my precious earnings

for food,” she said. “A nickel glass of jelly and a five-cent loaf of bread

made very good eating while I was looking for work. A couple of slices of bread

and a glass of water made a good meal, and when the jelly was added, I had a

party!”

In 1921, Bell – who called herself Elaine – graduated with

honors from St. Athanasius, and then made her way north to study teaching at

Atlanta University Normal School.

“When I was going to Atlanta University my shoes wore out …

the soles went completely and the outer rim spread like a moccasin’s mouth,”

she said. “When students made fun of my feet, I held my head high and craned my

neck to peer into the distance to see what was giving them so much fun.”

She graduated from Atlanta University, raggedy shoes and

all, and was Salutatorian of her class.

Her early teaching career included six years (1923-1929) in

the public schools of Winston-Salem, N.C. While teaching in North Carolina, she

would go to New York City during the summers to work for a family. She made

more money in the summer in New York than she did teaching school in North

Carolina.

“I bought clothes, shoes, hats, luggage, and silk

underwear, and sent money home to Sapelo, as much as $40 at a time,” she said. She

paid for her sister Kate’s sewing lessons and began saving to buy a new home.

She went back to school, this time in Indiana, and in 1930 earned

a Bachelor’s degree in English and Science from Ball State Teachers College

(now known as Ball State University) in Muncie, Indiana. That same year, she

returned to Atlanta to join the faculty of a groundbreaking experiment in

education known as Atlanta University Laboratory School.

Atlanta University Laboratory School opened in September of

1930. The school combined the college preparatory programs of Spelman College,

Morehouse College and Atlanta University.

The secondary school students took classes in Giles Hall on

the Spelman campus.

Elementary school children attended classes at Oglethorpe

School which was on the Atlanta University campus.

Elizabeth Elaine Lemon served as the Teaching Principal of

the laboratory elementary school, from 1930-1943.

The philosophy of the progressive school included

independent study with a social-problems approach, and the belief that students

should have a role in choosing the topics to be studied and help plan class

projects. The school was governed by collaboration or a democratic process amongst

the faculty members, who met weekly, as well as the students.

The school attracted talented faculty and gifted students who

often received state and national recognition in the areas of science and

writing.

In an article published in The New York Age in 1931, Atlanta University president, John Hope,

described the purpose of the laboratory school.

“It’s purpose is not primarily to give students in the

Department of Education practice in teaching,” he said. Rather, it is to

“provide them with an opportunity to observe good teaching and its

results.”

One of the most distinguished teachers was artist and

Harvard graduate Hale Woodruff, who was the chair of the Art Department

One of the most distinguished students – although he was

only in the seventh grade at the time -- was an overachiever named Martin

Luther King, Jr. (Young Martin, by the way, would ultimately skip ninth-grade

and finish his high school years at Booker T. Washington High School in Atlanta,

before entering Morehouse College at age 15.)

Elaine Lemon, who was one of Martin Luther King’s teachers,

had a personal teaching style that involved getting outside and going places.

In addition to reading, she encouraged learning through experimentation and

dramatization.

The Atlanta University Laboratory School had its critics. Renowned

author, sociologist, and activist W.E.B. Du Bois, who was on the faculty of

Atlanta University, viewed the program with some skepticism, primarily because

he felt the school was understaffed and underfunded. In addition, the student

population did not reflect the socioeconomic and educational diversity within

the African American community. The students at the Laboratory School were the children

of successful business owners and preachers, attorneys, doctors, and teachers.

An article published in The

Atlanta Constitution in 1979 described the Laboratory School’s Oglethorpe

Elementary as the first step on the road to entry in the “black society.” The

next step was the Laboratory High School, and then Spelman or Morehouse, before

going off to graduate school.

The story of experimentation in black high schools in the

1930s and ‘40s, and the history of the education of African Americans, is worth

a Black History Month program all by itself. Elaine Lemon was part of a progressive

movement known as the Secondary School Study or the Black High School Study. It

included the Laboratory School and 17 other high schools throughout the South,

and her participation in this experiment undoubtedly shaped her philosophy as

she continued her career in education.

While teaching in Atlanta, Elaine Lemon continued going to

school during the summers and during leaves of absence, she would take from teaching.

She continued working other side-jobs to help pay her way through school, but

she no longer had to clean houses.

She earned her Master’s degree in Social Science from

Columbia University in New York in 1941, where she was elected Dean’s Scholar

in the Advanced School of Education in the Teachers College. She taught

religion at the historic Riverside Church also in New York not far from

Columbia, as well as at Chautauqua Institution in New York, and Tufts College

in Boston.

When the United States entered World War II, Elaine Lemon

switched gears and became a USO director, coordinating services for American

troops and helping to boost morale.

Following the war, she went back to Indiana and taught in

a public school. In 1953 she was named the first African-American principal of

the new $1 million Frederick Douglass School in Gary, Indiana, where she served

until she retired.

Retirement for Elaine did not mean rest. She continued

learning and teaching, with the whole world as her classroom. She traveled to

five continents as a YMCA World Ambassador in the mid-1970s and into the 1980s.

In India, she met the prime minister, Indira Gandhi. In

Ghana, she helped to build a school for preschoolers. She visited Tanzania,

Nigeria, and Uganda, Greece, Italy, and the People’s Republic of China. She

visited countries in Europe and Central America. In 1982 she visited the Soviet

Union.

Back in Gary, Indiana, Elaine was active with the Urban

League, the YWCA, the PTA, the United Way, the Chamber of Commerce, and the

Friends of the Library. She was a member of Sigma Gamma Rho Sorority, a

lifelong member of the NAACP, and an inspirational speaker. Her speaking topics

included everything from the meaning of life to the role of women in the Space

Age.

She was mentioned on the Society pages of Jet Magazine at least twice for her fundraising

work with the United Negro College Fund and for her travels abroad.

When Elaine Lemon returned to Coastal Georgia, she made

Savannah her home. She lived in the house she had bought many years earlier.

(Yes, she did buy that house she was saving for all those years ago. It was a

home where her mother lived out the last years of her life.)

In Savannah, she was an active member of St. Matthews

Episcopal Church. She taught Sunday School and was a member of the St. Augustus

Guild and served on the Day Care Center Board.

Elizabeth Elaine Lemon died on New Year’s Day in 1999, in

Savannah.

The gifted teacher had touched lives and inspired so many halfway

across the country and around the world. Her funeral program read: “Bell, our

beloved sister, aunt, cousin, and friend.”

She was an extraordinary woman. At the same time, she was

like so many African American men and women of her generation … the

grandchildren of enslaved people who fought to be free and control their own

destiny.

Black people who rode the wave of the Great Migration from

the South to the North and West, running from Jim Crow, searching for

opportunity, building new lives.

Elizabeth Elaine Lemon was the product of a family that

loved her, and an island community of friends, teachers and a church-family that

nurtured her and instilled in her the desire to succeed and to serve.

Looking back, when she had time to reflect on her life, she

understood the odds she overcame and the hard work she did to reach her goals.

“Would you believe that it is just in later years that I

realized that my going to school was a heroic undertaking?” she reflected in an

interview with genealogist Mae Ruth Green.

“I was working to send myself to school since I was in the

fifth grade. I lived with people who worked me morning, noon, and night. I ate

sparingly hoping they would notice and lighten my work … but they did not see.”

We see

you, Bell, and we thank you, and we honor you for your perseverance and commitment.

She left her island home all those years ago, but she took

Sapelo with her. All the love and discipline and determination that was poured

into her, she poured into the world, and into the people whose lives she

touched.